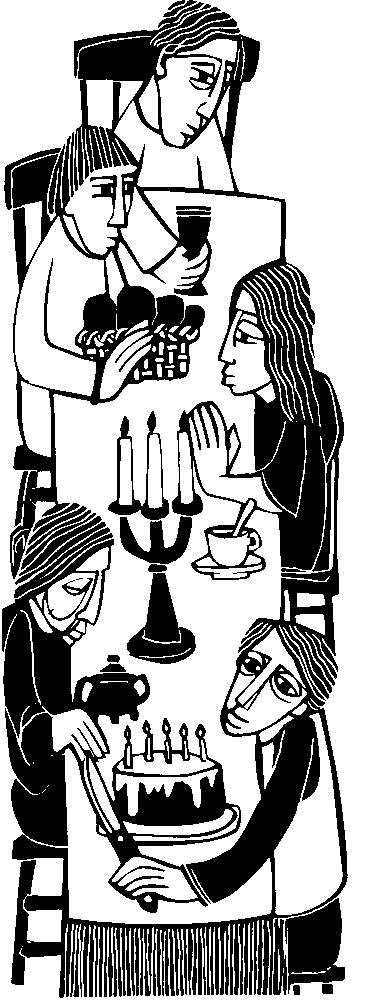

On God’s mountain all people are given a banquet of rich food

and fine, aged wine. Mourning and death cease, and every tear is wiped

away. Shame is dispelled; hunger is forgotten.

“This is our God, in whom we hoped for salvation.” Thus Isaiah recalls the lush image of the banquet, that same feast of which the psalmist sang, with food prepared in abundance, cups running over, heads anointed with oil. It is the banquet of God that, despite transient appetites or hungers, allows Paul to be satisfied no matter what his need or desire. “In him who is the source of my strength I have strength for everything.”

In the context of heaven’s feast, the Gospel of Matthew presents a strange story, one among many instances, actual or symbolic, of dinners and banquets.

In this particular case, some of the invited are uninterested in the banquet prepared for them. Others make light of it and go about their business; still others ridicule and abuse those who bring the offer. So the king sends his wards out into the streets to invite everyone, good and bad alike, into the banquet. Eventually, however, the king spots a visitor who is not wearing a robe, and the poor bloke is cast into darkness.

This has never been a very attractive story for me. It seems somewhat mercurial and vindictive. Why invite people to the banquet if you are going to reject them? Were not all called and welcome?

It is understandable that those who absolutely reject Christ and the bounty of his saving banquet are not included. They do not even want to come to the party. But the rest—all those who do not resist the possibility that God calls them to the eternal feast—are welcomed.

So why are some people who are already in the promised banquet-land excluded for the feeble-sounding reason that they are improperly dressed?

What has helped me understand this odd state of affairs is CS Lewis’s wonderful fantasy, The Great Divorce, which he wrote to suggest that the option between heaven and hell is a radical choice we all have.

In this short, allegorical story, it turns out that a group of people, after a long bus ride, find themselves in a strange location. It is the vestibule of heaven itself, a place they have all generally wanted to go. The problem is that they must now believe that they are actually there. They must accept the fact that God really saves them.

Lewis develops a lively drama for each traveler’s life. All they need to do is “put on” the armor of salvation to receive it; yet many of them cannot bring themselves to believe that they are in banquet-land. They would rather cling to the defenses with which they have covered themselves during their lives.

One self-pitying chap, unwilling to let go of the mantle of his own righteousness, just cannot bring himself to trust that he is actually within the gates of Paradise. He grips his resentments so tightly that he disappears into the small dark hole of his egotism.

Another poor soul wears a small, slimy red lizard on his shoulder, a twitching, chiding garment of shame and disappointment. This lizard is his clothing, his self-image and self-presentation to the world. It is a symbol, Lewis leads us to believe, of some sin of lust, which the pilgrim soul both hugs for identity and carries for self-pity.

An angel approaches, offering to kill the slimy creature, which protests that if he is killed, the soul will surely lose his life and meaning. The ghost-soul, encouraged by the angel, finally lets go of the lizard, but only with trembling fear. He gasps out a final act of trust: “God help me. God help me.”

And with that plea, a mortal struggle ensues, the lizard mightily resisting while a wondrous metamorphosis happens. The lizard is transformed into a glorious creature. “What stood before me was the greatest stallion I have ever seen, silvery white, but with mane and tail of gold. ... The new-made man turned and clapped the new horse’s neck. ... In joyous haste the young man leaped upon the horse’s back. Turning in his seat he waved a farewell, then nudged the stallion with his heels.” They both soar off, like shooting stars, into the mountains and sunset.

What happened to this wayfarer at the vestibule of the banquet is that he finally clothed himself in Christ rather than in his shame. Having nothing of his own, not even his sins to cling to, he abandoned himself in the “God help me” of radical trust.

If it is God’s will that we all be saved in Jesus, then it is for us, clothed in faith, hope, and love, to accept God’s will as our own. Perhaps this is the meaning of Jesus’ parable, as well as of Lewis’s.

Paul wrote in his Letter to the Galatians that if we are baptized in Christ, we must be clothed in him. Christ is the only adequate banquet garment. And it is his love, as we read in the Letter to the Colossians, that must be the clothing to complete and unify all others we wear. Yes, every child of the earth is called to the feast. But if any of us actually get there, it will only be because we are “all decked out” with Christ, in God.