Reading I: Genesis 15:5-12, 17-18

This reading combines three different themes: Yhwh’s promise of an abundant posterity to Abraham; his

promise of the land to Israel; and the sealing of that promise with a covenant ceremony.

The Book of Genesis contains several stories of God’s establishment of his covenant with Abraham, all of

them variants of the same tradition.

In Abraham, God decisively intervened in human history to create a people for himself. God’s choice is,

on his side, a sheer act of grace; and faith is set, be it noted, not in the context of individual salvation,

but in the context of a people’s history.

This is the context in which the Old Testament views sola gratia, sola fide.

The apostle Paul discerned the fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham in the Christ-event and in the

emergence of the new Israel, the Church (Gal

3; Rom 4).

Responsorial Psalm: Psalm: 27:1, 7-8, 8-9, 13-14

This psalm serves as a link between the first two readings. The fourth stanza begins with the words: “I

believe that I shall see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living!”

For Abraham this land was eretz Israel, the territory that his descendants were destined to occupy.

For Christian believers this land is the kingdom of God, the “commonwealth of heaven” of which the

second reading speaks.

Reading II: Philippians 3:17-4:1 or 3:20-4:1

Both the Second Reading and the Gospel speak of a “change.” The Second Reading speaks of the

change of our earthly existence in the final consummation; the Gospel speaks of the change of Jesus as he

prayed on the holy mountain.

The term “glorious body,” like the term “spiritual body,” which Paul uses in 1 Corinthians, chapter 15, reflects

the apocalyptic hope. According to this hope, the life of the age to come will not be merely a prolongation of

this present life but an entirely new, transformed mode of existence. It was into this mode of existence that

Christ entered at his resurrection.

But his resurrection is not merely an incident in his own personal biography, as it were; he entered into that

existence as the “first fruits” (1 Cor 15:20), that is, as the one who made it possible for believers also to enter into

that new mode of existence after him.

That is the Christian hope.

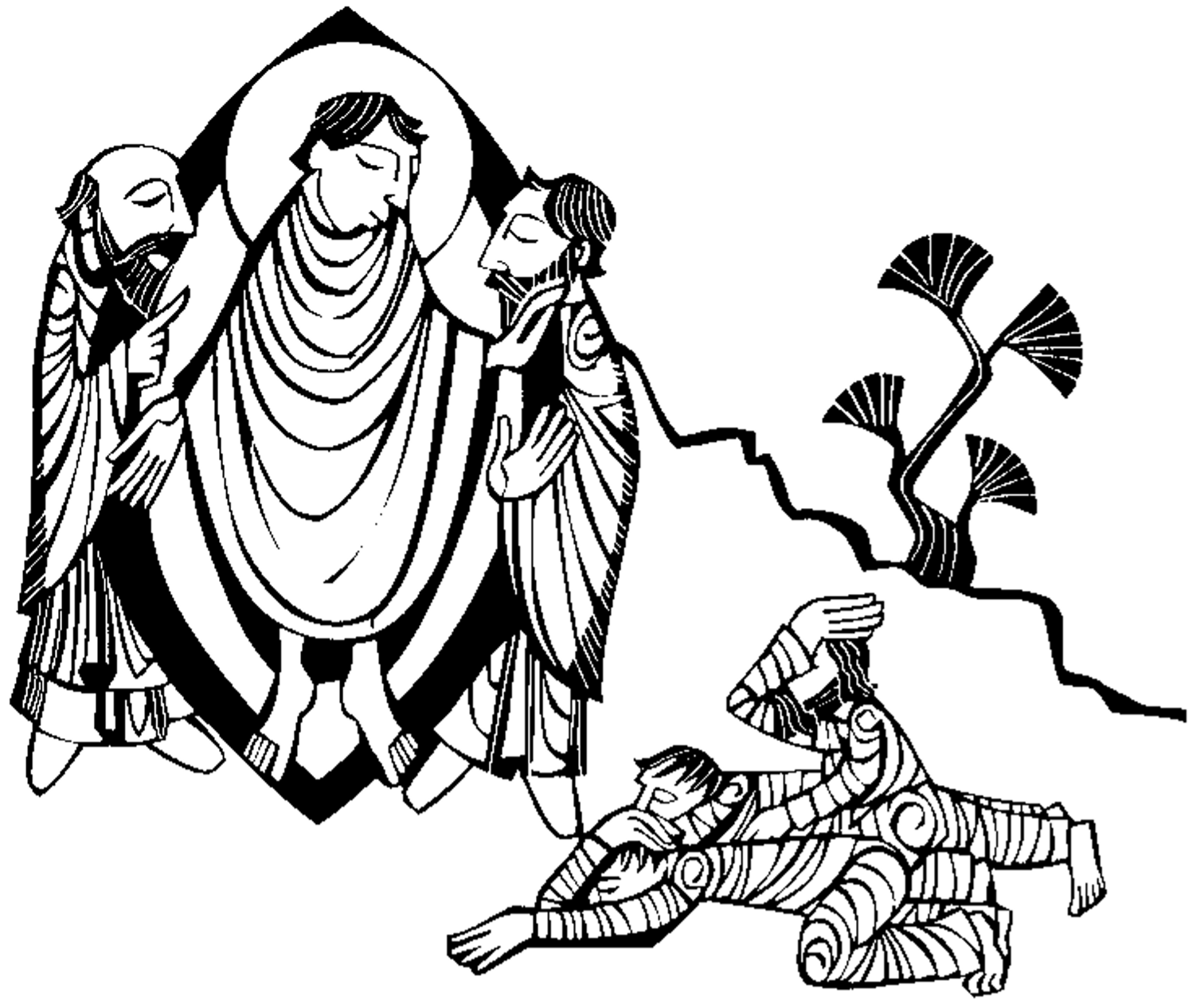

The use of the transfiguration story on the second Sunday of Lent in the revised Roman Lectionary follows the

tradition of the Missale Romanun.

The Episcopal, Lutheran, and Methodist Lectionaries depart from the Roman Lectionary here and read the

transfiguration story on the last Sunday after Epiphany. On that day it forms an admirable transition from the

contemplation of the earthly ministry of Jesus as the manifestation of God in the Epiphany season to a

contemplation of the passion as the ultimate epiphany.

In the Roman Lectionary the transfiguration story serves the theme: “Behold, we go up to

Jerusalem.”

That Jesus and his disciples ascended a mountain for solitude after the abrupt conclusion of his Galilean

ministry, and that Jesus communicated to his disciples his change of plan—which was to go up to Jerusalem and

challenge the religious authorities in the nation’s capital—is historically plausible.

This original nucleus of historical fact was then rewritten by the post-Easter community in the light of its

Easter faith. There is some indication in the Gospels of an awareness that the events of Jesus’ earthly

life appeared in a different perspective after the first Easter (see Jn 2:22; 12:16). Thus, what happened on the mountain

was rewritten with the use of Old Testament materials.

The change in the appearance of Jesus’ face is reminiscent of Moses on Mount Sinai (Ex 34:29). Moses and Elijah, both of whom

figured in first-century Jewish apocalyptic as returning at the end, talk with Jesus about his

“departure” (Greek: exodos), that is, his death and exaltation.

The disciples were ready enough to accept Jesus as one of the end-time figures, along with Moses and

Elijah, but not yet as a unique figure of the end-time. So a voice from heaven proclaims the finality of

Jesus: “This is my Son, my Chosen; listen to him” (note the allusion to Deut 18:15).

Then we are told that after this “Jesus was found alone.” The story as retold by the post-Easter

Church is rich in symbolism, proclaiming that Jesus is the Son of God, his final emissary, and the second

Moses, who accomplishes the new Exodus.

The addition of the words “at Jerusalem” in Luke 9:31 looks like a redactional addition, for it is one of Luke’s major themes

that the holy city is the focal point to which the ministry of Jesus moves. It is there that the saving event

is accomplished, and it is from there that the proclamation of that saving event goes forth to the ends of the

earth.

The point of all this is that the gospel proclaims, not a timeless myth (see 2 Pet 1:16, also about the

transfiguration), but something that actually happened at a particular time and place in history.