Reading I: Deuteronomy 18:15-20

In the original intention of the Deuteronomic author, the “prophet” whose coming Moses

predicts stood for the prophetic office as such, exercised by a whole series of prophets in Israel.

They were understood by the Deuteronomist as standing in a charismatic succession from Moses.

Later on this text was interpreted eschatologically in certain circles of pre-Christian Judaism, as

we see from the Dead Sea Scrolls (1 QS 7) and from the evidence of the Fourth Gospel (John 1:21; 6:14; 7:40).

In these circles Deut

18:15 was interpreted as a prediction that God would send one final prophet (the

“eschatological prophet,” as modern scholars call it).

Jesus’ own self-understanding, though perhaps not quite so explicit, was in line with this,

for he understood his mission in terms of proclaiming the dawning of God’s kingdom, and

himself as the last messenger before its consummation. It was apparently left to the earliest

post-Easter community to work out an explicit Christological interpretation of Jesus in terms of the

eschatological prophet like Moses (see especially Acts 3).

As originally intended, this was a high Christology, emphasizing not only Jesus’ authoritative

teaching but also his agency of redemption, just as Moses had led the Israelites out of Egypt as the

agent of God’s earlier act of redemption.

When Christianity moved to the Hellenistic world, this early Christological title seemed inadequate

and was replaced by such titles as Kyrios, Son of God, and Logos.

The selection of Deut 18:15-20 for today seems to have been determined by the allusion to

Jesus’ teaching with authority in the Gospel reading.

Responsorial Psalm: 95:1-2, 6-7, 7-9

The Venite consists of two parts: a call to worship and a warning against neglect of the

word of God. The first part is very popular among Anglicans as the invitatory canticle of Morning

Prayer, but in most recent revisions the stern warnings of the second part have often been

omitted.

Yet, it was this second part that the author of Hebrews (Heb 3:7-4:13) took up as

especially relevant to his Church. The situation of the people of this Church was that they were

growing stale instead of advancing in the Christian life, just as Israel grew weary in the

wilderness.

These same verses are used on the third Sunday of Lent in series A and on the eighteenth Sunday of

the year in series C. Today the refrain serves to pick up the warning to give heed to the prophet

like Moses.

Reading II: 1 Corinthians 7:32-35

One can only speculate what motives led to the choice of the caption, which speaks of the advantage

of the unmarried state to women and, unlike the text, says nothing about men!

Paul’s views on marriage and celibacy cut right across the views commonly held by Christians

today. He commends celibacy for both men and women, but regards marriage as perfectly lawful and

proper for any Christian. At the same time, however, he has a distinct preference for celibacy.

Both states have their advantages and their perils, but on balance, according to Paul, the celibate,

whether man or woman, is less likely to be distracted from the service of the Lord.

At the same time, certain points of difference have to be noted about Paul’s teaching on

celibacy compared with that of later times. Paul refuses to lay down a hard and fast rule (1 Cor 7:35: “not

to lay any restraint upon you”). The celibate life requires a charism that not every Christian

has (see 1 Cor 7:7).

Yet, against much contemporary post-Freudian opinion, Paul clearly believes that celibacy is the

higher state. This is seen from what he says in other parts of this chapter (1 Cor 7:6, 7:8, 7:25, 7:38).

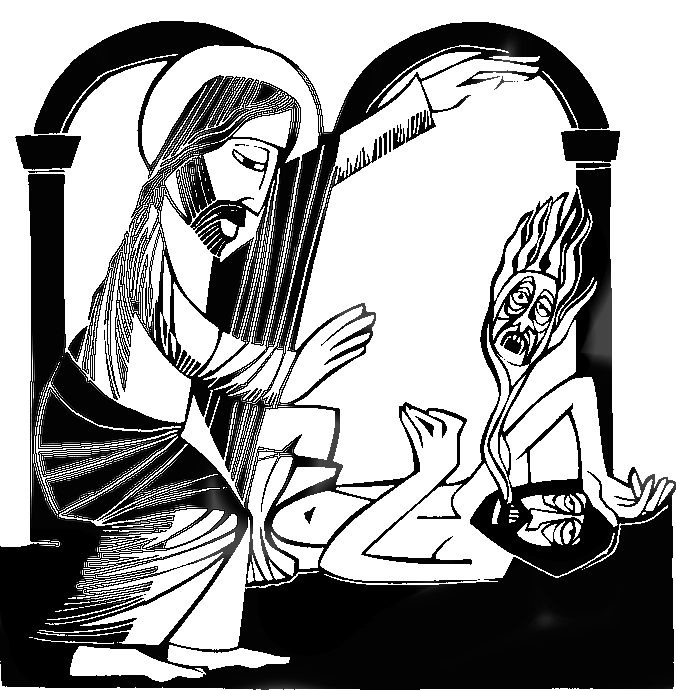

This passage follows immediately upon last week’s Gospel reading. After

the call of the first disciples, Mark has Jesus embark upon his public ministry in Galilee. The

first item of material that Mark selects for inclusion from his material is an exorcism. Perhaps the

miracles he includes from Mk

1:20 to 3:12 are from an earlier collection of miracle stories that he edited and

supplemented with other non-miracle material.

One special feature of this editorial work is the evangelist’s emphasis on Jesus’

teaching, though without indicating the content of that teaching. The effect of this is to play down

the one-sided emphasis on the miracles that such a pre-Marcan collection of miracle stories might

have created. The Marcan tradition saw the miracles as displays of Jesus’ authority.

The Greek word for “authority” in the “choric ending” of the exorcism story

is exousia. This word also has the connotation of power, particularly in this context of

miracle. Mark does not deny that Jesus displayed both authority and power in his miracles, but for

him the miracles were only one aspect of Jesus’ authority.

The primary emphasis rests upon his teaching: “he taught as one who had authority

[exousia—the word is picked up by the Marcan redaction from the body of the exorcism

story], and not as the scribes.” The exorcism follows merely as an illustration of the power

of Jesus’ teaching with authority. “In Jesus’ word heaven breaks in and hell is

destroyed. His word is deed” (Eduard Schweizer).