“Are they trying to make the Catholic Church a peace church?” This sentiment was among the reactions to the pastoral letter that our U.S. bishops issued some years ago, called The Challenge of Peace (1983). I recall finding that response provocative and illuminating. I knew what the speaker meant: there are Christian denominations such as the Quakers and Mennonites that have made peacemaking and even pacifism a dominant theme in their devotion and action; and no historian has ever grouped Roman Catholics in that category.

But as soon as I recognized that fact, I had to ask, “Why not?” Is not peacemaking central to the teaching of Jesus? There was no doubt of that in our bishops’ minds when they wrote their peace pastoral. And they were echoing powerful statements from recent popes. (“If you want peace, work for justice,” said Pope Paul VI.)

Each of this Sunday's readings invites us to ponder the centrality of peace and justice in the mission of Jesus and in the mission of any of us who claim to be his disciples.

The selection from Isaiah contains the famous figure of the Servant of Yahweh. Commentators have debated long and hard whether this servant stands for Israel as a whole or for an individual within Israel. The consensus now is that, in the full context of Isaiah 40-55, the servant stands for both; that is, the figure of the servant represents Israel in her mission to be a light to the nations, and at the same time the language points to the role of a person within Israel who enables her to fulfill that mission. The poem is written as a divine oracle, and the words promise a special endowment of the Spirit of God, thus marking the mission as prophetic. It is also in the language of kingship (“establishing justice on the earth”), with the startling difference that this reign will come about not through military conquest but through conspicuously nonviolent means (“a bruised reed he shall not break, and a smoldering wick he shall not quench”).

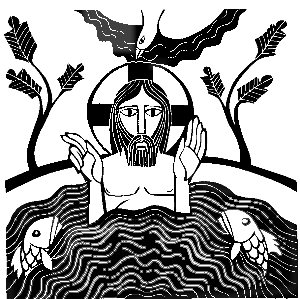

The Gospel account of the baptism of the Lord alludes to this passage from Isaiah by combining the descent of the Spirit of God with the divine voice’s reference to the Son “with whom I am well pleased” (Matt 3:17; Isa 42:1). Against this background, the exchange between John the Baptist and Jesus, unique to Matthew’s account, makes profound sense. Attempting to prevent Jesus from joining the conversion ritual, John says, “I need to be baptized by you, and yet you are coming to me?” To which Jesus replies, “Allow it now, for thus it is fitting for us to fulfill all righteousness.” Does this exchange recall otherwise neglected sayings of John? More likely it is an expansion by Matthew, answering a doubt some may have had about the propriety of the Baptist seeming to have a superior role here.

The clarification is profound. The question of superiority is secondary to the fact that each is “fulfilling all righteousness”—a word special to Matthew's Jewish vocabulary meaning to do the will of God. Here righteousness means especially to carry out the peace and justice mission articulated in the Servant passage echoed by the heavenly voice. It is the righteousness spelled out concretely in the Sermon on the Mount (see Matt 5:6, 10, 20; 6:33), where Jesus clearly calls his followers to nonviolence and love of enemies.

When Luke summarizes the meaning of the baptism of the Lord in the speech of Peter to Cornelius's household in Acts, he draws on this same portrait of the Servant in Isaiah.

You know the word [that God] sent to the Israelites as he proclaimed peace through Jesus Christ, who is Lord of all, what has happened all over Judea, beginning in Galilee after the baptism that John preached, how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the holy Spirit and power. (Acts 10:36-38)

The thrust of this biblical teaching suggests that any community calling itself Christian is necessarily called to be, in a profound sense, a peace church. Our Pope and bishops have been trying to call our attention to this for some time now.