In the Eastern Church, the primary emphasis of Epiphany was theological rather than historical: the epiphany of God in the humanity of the incarnate One. Indeed, the whole life of Christ was a series of epiphanies, of which his baptism was the first and most important.

The original prominence of the baptismal epiphany was never completely forgotten in the West, but it was relegated to a corner in the liturgy—in the Roman Missal, to the gospel for the octave; in the Book of Common Prayer of 1928, to an office lesson.

The revisers of the calendar could hardly have been expected to restore the baptism to its Eastern prominence by putting it on the actual day of Epiphany. The story of the Magi is too popular Western Christian lore for that.

In the present calendar, the baptism is celebrated on the Sunday after January 6 if this Sunday does not coincide with Epiphany; if it does coincide, the baptism is transferred to the Monday after Epiphany.

Thus, the feast has regained some prominence, and for this we may be glad. It helps to reinforce the theological, as opposed to the historical, emphasis of our Western Christmas cycle of feasts.

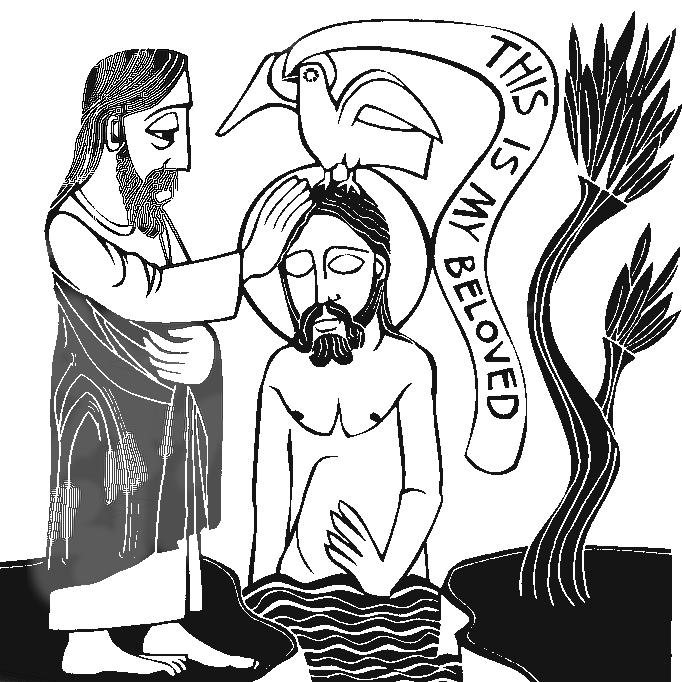

This passage, the first of the servant songs in Second Isaiah, has deeply impregnated the Gospel narratives of our Lord’s baptism. The heavenly voice at the baptism (“This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased”) is, in part at least, an echo of the words “in whom my soul delights” (Is 42:1).

The word for “beloved” may be an alternative rendering of “chosen,” and it is held by some that the word “son” is based on an ambiguous rendering of the original Aramaic word for “servant.”

Note that Mt 12:18 has a formula quotation of Isa 42:1-4 as an explanation of Jesus’ command to the healed not to make him known, the emphasis here being on Is 42:2-3 in the Isaian prophecy.

The original identity of the servant is a much controverted question. Some think that he represents the whole nation of Israel; others, a faithful remnant; and still others, an individual figure—the prophet himself, or some prophet or king of the past, or perhaps a messianic figure of the future.

What the original meaning was need not concern us here. In the liturgy today, as in the evangelists, the servant is identified with Jesus, who is manifested as such in his baptism.

The latter part of the song speaks of the work of the servant: to establish peace on earth, to be a covenant to Israel and a revelation to the nations, to open the eyes of the blind, and to proclaim the liberation of captives.

This forms a suitable introduction to the stories from the earthly ministry of Jesus that will be read between now and the beginning of Lent. Jesus’ words and deeds are an epiphany of the servant of the Lord.

[Webmaster note: This commentary was written for Reading V of the Easter Vigil]

This reading is an invitation to the eschatological banquet anticipated in the paschal Eucharist: “Come, buy and eat! Come, buy wine and milk” (Is 55:1). It is the feast of the new covenant (Is 55:3) with the messianic king (“my steadfast, sure love for David,” Is 55:3). In this banquet the presence of Yhwh is near (Is 55:6) and available for participation—but on one condition: penitence and the reception of pardon for sin (Is 55:6-7).

For this moment all of our Lenten devotions, our going to confession and receiving absolution, have been preparatory; all these exercises are gathered up into this reading.

God’s ways transcend all our ways (Is 55:8). He calls into existence things that do not exist, and he gives life to the dead (Rom 4:17). He has raised Jesus from the dead and has raised us from the death of sin to the life of righteousness (see the epistle).

In the mission of Christ, God’s word did not return to him empty but truly accomplished that which he had purposed in sending it (Is 55:11).

Responsorial Psalm: 29:1-2, 3-4, 3, 9-10

In some ways this psalm is like the other enthronement psalms we have encountered, for it celebrates the kingship of Yhwh (“the Lord sits enthroned as king for ever”). But there are differences.

The second stanza suggests that the psalm had its origin in a pagan hymn to Baal-hadad, the storm god of Canaan. Its meter also recalls Canaanite poetry as known from Ugaritic texts. But if that was its origin, the hymn has been thoroughly baptized: the storm has become an epiphany of Yhwh, the Creator-God.

In its present liturgical context, however, the hymn acquires yet another meaning. “The voice of the Lord upon the waters” suggests a voice from heaven at the baptism of Jesus. So the psalm becomes a celebration of the epiphany of God that takes place at the baptism of Jesus.

Responsorial Psalm: Isaiah 12:2-3, 4bcd, 5-6

[Webmaster note: This commentary was written for the Responsorial Psalm following Reading V of the Easter Vigil]

Although this passage (the first song of Isaiah, Ecce, Deus) occurs in Proto-Isaiah, its spirit is more akin to Deutero-Isaiah. It celebrates the return from exile as a second Exodus and is a new song, patterned on the original song of Moses, as the close verbal parallelism between the third stanza and Ex 15:1 shows.

As in Isaiah 55:1-11, we have here the same fourfold pattern: exodus/return from exile/Christ’s death and resurrection/the foundation of the Church and our initiation into it through baptism and the Eucharist.

This passage comes from one of the kerygmatic speeches of Acts, that is, formulations of the kerygma, or preaching of the early Church. It is remarkable as the only reference to Jesus’ baptism outside the Gospels. Like Mark and John, it presents that event as the beginning of Jesus’ story.

In his baptism he is anointed with the Holy Spirit and so equipped for his ministry of healing and exorcism. Note how the history of Jesus is told as a series of acts of God. It is God who preaches the good news of peace in Jesus Christ, God who anoints him, and God who is with him in the performance of his miracles.

It is often held that there is a radical difference between the message of Jesus and the proclamation of the early Church. Jesus preached the kingdom, but the Church preached Jesus.

There is certainly a formal difference here but not a material one.

In proclaiming the kingdom, in performing exorcisms and healings, Jesus was witnessing to the presence of God acting eschatologically in his own words and works. And in proclaiming Jesus, the Church, as we can see from the present reading, was proclaiming that God had been present in Jesus’ word and work.

The Church proclaimed Jesus precisely as the act of God, the epiphany of his saving presence. This epiphany is activated at the baptism.

This reading overlaps with the traditional epistle for the old Low Sunday, which was 1 John 5:4-10. By beginning with verse 1, the reading latches on to the paschal theme of baptism: “Jesus is Christ (Messiah)” was a primitive baptismal confession, and it is in baptism that believers become children of God.

This carries with it the responsibility to love God and neighbor.

Then, in the typical “spiral” style of the Johannine school, the author reverts to the theme of baptismal rebirth and adds a new point, namely, that through baptism we overcome the world. “World” in Johannine thought means unbelieving human society organized in opposition to God and subject to darkness, that is, sin and death.

The writer then makes the tremendous statement that Christian faith overcomes the world. As he immediately makes clear, the faith he is talking about is not a dogmatic system but an existential trust in Jesus Christ as the Son of God, the revelation of God’s saving love.

Such faith points beyond itself to its object—the saving act of God in Christ. That is the real victory that triumphs over unbelief.

This point is reinforced by the final paragraph, the perplexing passage about the three witnesses: the Spirit, the water, and the blood. A clue here is that the statement has a polemic thrust—it refutes those who say that Jesus Christ came by water only, not by water and blood.

“Came by water” is probably a reference to Jesus’ baptism: “came by blood,” to his crucifixion.

There were false teachers in the environment of the Johannine Church who asserted that Christ was baptized but not crucified. This may refer to a Gnostic teaching that Jesus was a mere man on whom the divine Christ descended at his baptism, then left him before his crucifixion. A modern analogy would be those who base their whole theology on the incarnation and ignore the atonement.

The first paragraph consists of John’s messianic preaching; the second is Mark’s version of the baptism of Jesus.

The content of John’s messianic preaching can be discussed at two levels: at the level of the “historical Baptist” and at the level of post-Easter Christian interpretation.

At the historical level, John pointed to the coming of a stronger one (Yhwh himself or a distinct messianic figure?—the answer is not clear), and he spoke of this stronger one as a judge (baptism with fire in Q; Mark’s “Holy Spirit” is clearly a Christianization, but “Spirit” could mean “wind,” another image for judgment).

It is historically unlikely that John recognized Jesus as the Coming One (see the Baptist’s question in Mt 11:3 and parallels, and note also the modern critical view that Jesus’ earthly life was only implicitly messianic, the expressly messianic interpretation of his person having arisen only after Easter).

Similarly, we can discuss the significance of Jesus’ baptism on the historical level. That Jesus was baptized by John is a fact beyond all reasonable doubt (although it has occasionally been questioned), for it caused much embarrassment to the early Christian community, especially in controversies with the continuing followers of the Baptist.

The clue to its interpretation lies in Jesus’ subsequent conduct.

After his baptism he broke away from John and embarked upon a career of eschatological preaching and a healing ministry distinct from John’s mission. Historically, therefore, Jesus’ baptism must have meant for him a call to this mission. In various ways Jesus alludes to the decisive significance of his baptism (see, for example, the question of authority in Mark 11:27-33 par.).

In Mark’s Gospel, these two traditions—John’s messianic preaching and Jesus’ baptism—have been Christianized.

First, the two traditions have been tied closely together. This shows that for Christian faith, Jesus in his baptism is marked out precisely as the stronger one whose coming the Baptist had predicted.

Second, the stronger one becomes, even in John’s preaching, a savior rather than purely a judge; he baptizes with the Holy Spirit rather than with fire.

Third, the baptism of Jesus is interpreted in an explicitly messianic sense by two narrative devices: the descent of the Spirit like a dove and the voice from heaven.

Here many Old Testament passages have contributed to the narration: the rending of the heavens, Is 63:11; the descent of the Spirit upon the Messiah, Is 11:2; the voice from heaven, Ps 2:7 and Is 42:1. The Christology of the voice from heaven combines the motifs of the messianic Son of God and the suffering servant.

Mark, unlike Matthew and Luke, still describes the descent of the Spirit and the voice from heaven as inner experiences of Jesus rather than as objective events. Yet, he intends his readers to overhear the voice and share the vision. It is therefore improbable—though many have interpreted the passage this way—that Mark thought in adoptionist terms. The voice declares rather what Jesus is in his ensuing history.

In all that Mark proceeds to narrate about him, Jesus shows himself to be the Son and the servant of God. Thus Mark means us to read the baptism of Jesus as the first in a series of secret epiphanies, revealing to us, though not yet to Jesus’ contemporaries, the significance of the whole story that is to follow.

That story is the account of God’s eschatological act in Jesus, in his ministry and his death.

| Preaching the Lectionary: The Word of God for the Church Today Reginald H. Fuller and Daniel Westberg. Liturgical Press. 1984 (Revised Edition). |

|

|

For more information about the 3rd edition (2006) of

Preaching the Lectionary click picture above.

|

from Religious Clip Art for the Liturgical Year (A, B, and C).

This art may be reproduced only by parishes who purchase the collection in book or CD-ROM form. For more information go http://www.ltp.org