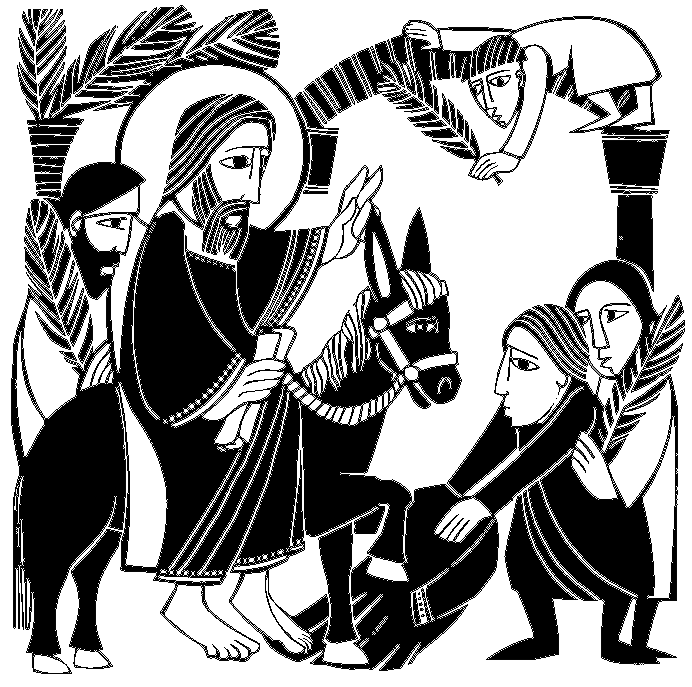

Passion Week commences with this Sunday's commemoration of the entry into Jerusalem and the reading of the Passion according to St. Luke. It is a time when the pageantry and the texts are so rich that there is little call for a full-bodied homily. It is usually enough for the preacher to help those assembled to focus on the ironies of the palm branches and the donkey. It can also be helpful to take a moment before the reading of the passion to attend to some of the nuances that make Luke’s account of Jesus' final days distinctive.

Here are a few details worth prayerful attention.

In his rendition of the Last Supper, Luke, alone among the Synoptic writers, includes a repetition of the argument among the disciples about which of them should be regarded as the greatest (Lk 22:24 = Lk 9:46). He then presents Jesus’ teaching on how Christian service should contrast with Gentile authoritarianism—a teaching that, in Mark, followed the third passion prediction. Why does Luke go out of his way to repeat the embarrassing spectacle of apostolic ambition—right in the middle of the Last Supper? And why does he postpone to this occasion the teaching on the service entailed in discipleship? The most likely explanation is that the evangelist wants to bring home to his readers that, for a community formed by the Eucharist, competition for preference is a scandal and mutual service is a mandate.

It is Luke who calls Jesus’ experience in Gethsemane

an agonia, which may carry the older meaning of

“fight” or “combat.” For in Luke's version,

the “grief” that Mark ascribes to Jesus is here

transferred to the disciples, and instead of shuttling between his

solitary, anxious prayer and his disciples and falling prostrate, here

Jesus kneels down, once, and prays simply (again, just once):

“Father, if you are willing, take this cup away from me; still,

not my will but yours be done.” Luke has chosen to underscore

Jesus’ decisive confrontation in prayer both with “the

cup” and his own resistance to it.

The Jewish leaders stress political elements in their charges: Jesus

is fomenting a tax revolt, is claiming to be a king, and stirs up the

people from Galilee to Judea. Pilate declares Jesus innocent of any

capital crime, a verdict that is echoed by the centurion under the

cross who says, “Truly this man was dikaios,”

which means both “righteous” (i.e., a keeper of all the

covenant relationships) and “innocent” (in the forensic

sense); both surely apply here.

It is Luke’s version of the crucifixion and death that gives us Jesus'

remarkable expression of forgiveness: “Father, forgive them;

they know not what they do.” For all of us who are challenged by

this radical modeling of love of enemies, it is helpful to note that

Jesus’ statement is a prayer. Whatever may have been

Jesus’ interior readiness to forgive, the fact that it is

expressed as a prayer of petition gives a helpful option to followers

of Jesus who find forgiveness of unrepentant adversaries next to

impossible. What may not come spontaneously from the human heart can

be requested in prayer.

The mocking of Jesus' messiahship is shared evenly between the

(Jewish) rulers and the (Roman) soldiers. They taunt the messiah and

king to save himself—at which point Luke notes the assertion of the

mutely articulate sign, “This is the king of the Jews.”

Luke's version is unique in showing the two crucified bandits picking

up that royal theme, each in his own way. One of them can only echo

the taunt of rulers, “Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and

us.” But the other turns the theme into an act of faith,

“Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” Then

Jesus, staying with the king theme, responds, “Amen, I say to

you, today you will be with me in Paradise” (a Persian loan-word

meaning “the king’s garden”). Luke omits the famous cry of

dereliction—“My God, my God, why have you forsaken

me?”—the only words we hear from the cross in Mark and Matthew.

Instead he records, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” Both sayings are quotations from Psalms. The first is the opening of Psalm 22, which moves from a sense of abandonment to a strong hope for vindication. The second is from Psalm 31, which also has the same movement, with the advantage of including the powerful expression of confidence carried in the quoted verse. Thus Luke helps us understand that Jesus' own experience and prayer could move from the darkness of near-despair to the light of complete trust in the Father.